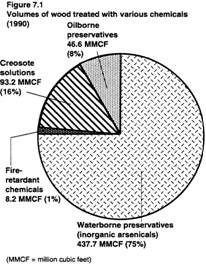

There are great differences in permeability to preservatives among individual species of softwoods and hardwoods. Some cells allow liquids to pass through them easily and into other cells and some do not. Several factors determine how permeable a particular piece of wood is:

Types of cells

Types of cells

Amount of ray cells

Amount of ray cells

- Types, size and number of pits

- Presence of extractives

Two other factors affecting a wood’s permeability must also be understood:

1 Whatever the shape or size of wood to be treated, preservatives can only get in from the outside. So the permeability of the outer cells is critical if they refuse to accept preservative, none can possibly penetrate to cells inside the wood.

2. In wood that is green (high moisture content) nearly all the cells are full or partially full of free water and the cell walls will also be saturated with bound water. Preservatives cannot be forced into such wood, so penetration and absorption will be negligible softwoods

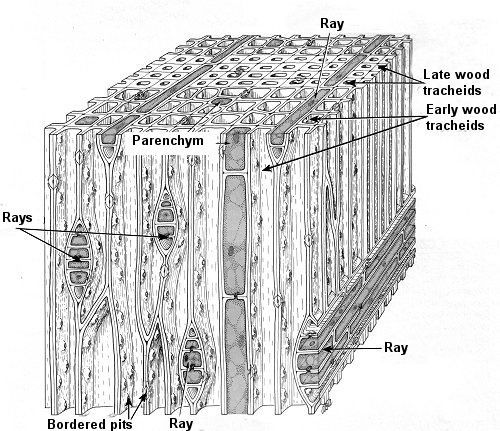

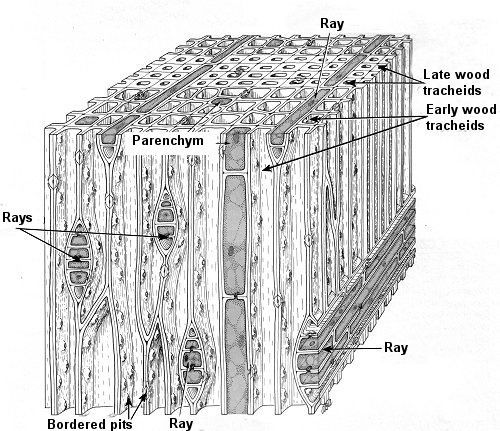

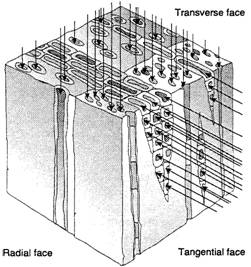

Look at the softwood cube illustrated in Figure. This is a greatly enlarged model of a tiny piece of dry softwood. What would happen if a real wood cube was dipped in a light petroleum oil carrier?

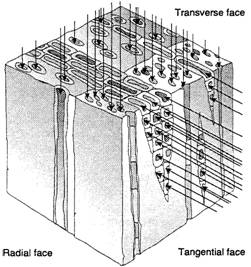

As Figure shows, the liquid would mainly enter four of the six faces of the cube, that is, the two cross-sectional or transverse faces and the two tangential faces. The two radial faces, which have no exposed open-ends of cells, will be relatively unimportant in absorbing liquids.

The cross-sectional faces expose end-grain or open tracheid cells to the oil. These tracheids, acting as hollow tubes, will accept liquid easily. Their small diameter actually encourages “sucking-in” of the liquid by capillary action, like blotting paper or a sponge. Oil will pass through the pits in the cell walls into adjoining tracheids.

The two tangential faces expose open ends of ray tracheid cells to the oil. The rays are also capable of capillary absorption of liquids, so they accept and transport the oil in a radial direction.

Within seconds of immersion in oil, the tiny softwood block will have absorbed perhaps enough oil to fill three-fourths of its cell cavities. How can this happen? What happened to the air that was in the block?

First, the capillary force is so strong it causes the air to squeeze up, or compress, in the cells. This allows space for the liquid oil. Second, some compressed air will escape through wider cells having less capillary pressure and will bubble out of the wood surfaces to make room for more liquid. Thus, the tiny softwood block will absorb a good proportion of its void volume in seconds, and most of the cells will receive some oil

In softwoods most preservative flow occurs by means of the vertical fiber tracheids and the horizontal ray tracheids. As these make up virtually all the wood volume, it is possible to fully saturate some softwoods with preservative

In hardwoods only the vessels and the ray tracheids can conduct preservatives. This often leaves extensive regions of fibers unprotected. As these give hardwoods much of their strength, this can be a very serious situation.

If preservation of this small cube of wood had been our objective and if the oil had contained a good wood preservative chemical, we could confidently say that the softwood cube had been well-preserved.

Hardwoods

Now let’s see what happens when we repeat the same experiment with a hardwood cube (See Figure). First, note the similarities between hardwoods and softwoods. Capillary action will suck oil into the open-ended cells of the two cross-sectional faces and the ray cells of the two tangential faces. Again, little oil will enter the radial faces.

Now note the differences from the soft-wood experiment. The cell ends of hard-woods, exposed by cutting the transverse faces, are of two types: vessels and fibers. Vessel segments, with large diameter cavitiesare joined end-to-end with other vessel segments to form long tubes (the vessels). In most hardwoods, oil will easily enter these vessels, and trapped air can bubble out from the wide cavities, allowing the vessels to fill with oil.

Fibers respond differently, however. If yourecall, they are narrow sealed cells that play no part in sap movement in the living tree. The fibers, exposed by the transverse sections, can readily accept oil by capillary suction, but they cannot easily pass it on to the other fibers. Consequently these fibers will not normally receive oil from the trans-verse sections.

As with softwoods, the hardwood ray cells are like open networks of tubing, able to absorb oil easily. The rays in most hardwoods are wider than those in softwoods, so a greater uptake of oil may occur in the rays. Also, the . rays can pass some oil to adjoining fibers, although the majority of fibers could remain dry.

Although quite a lot of oil may have been absorbed by the hardwood cubes, mainly in the vessels and ray cells, significant internal areas of the block (fiber areas) may have little or no oil. From a preservation standpoint,

there is a lot of unprotected cellulose and lignin in these fibers that is liable to decay. What is worse, as section above pointed out, the principal strength of hardwoods comes from these unprotected fibers.

The explanations of how liquid oil is taken up by these small softwood and hardwood cubes are also applicable to treating full-sized wood products. For example:

Even if pressure is not used in a wood-preserving process, capillary suction creates a negative pressure or partial vacuum because of the narrow diameter of wood cell cavities, so some liquid chemicals will be absorbed.

Even if pressure is not used in a wood-preserving process, capillary suction creates a negative pressure or partial vacuum because of the narrow diameter of wood cell cavities, so some liquid chemicals will be absorbed.

Air in wood cells can be compressed easily.

Air in wood cells can be compressed easily.

Air (compressed or not) is an obstacle to full impregnation of wood with liquids.

Air (compressed or not) is an obstacle to full impregnation of wood with liquids.

Rays and vessels in hardwoods and the fiber tracheids and rays in softwoods are the main routes for liquid flow into wood.

Rays and vessels in hardwoods and the fiber tracheids and rays in softwoods are the main routes for liquid flow into wood.

Fibers in hardwoods can act as a tight, impenetrable mass, which is difficult or impossible to treat with a preservative, depending on the species of wood. State Timber Corporation research division is conducting research on sri Lankan timber species penetrability.

Fibers in hardwoods can act as a tight, impenetrable mass, which is difficult or impossible to treat with a preservative, depending on the species of wood. State Timber Corporation research division is conducting research on sri Lankan timber species penetrability.

Methods of Applying Preservatives

Let’s discuss treating methods using a round fencepost of an easily-penetrated softwood species as an example of a wood product being treated with a selected preservative.

Brush-on and spraying

The simplest treating methods do not involve expensive equipment. We could brush or spray a post on all surfaces, expecting capillary action to give the preservative penetration into the wood. After several good brush coats, or sprayings and some obvious sucking-in of preservative, we would probably find that further absorption was negligible Additional applications would result in wet wood surfaces and there would be considerable run-off. If we sliced the post end-to-end, penetration by the preservative might resemble something like Figure. The deepest penetration is at the ends (transverse or cross-sections, where tracheid ends were exposed to the preservative liquid). Radial penetration into the post surfaces is shallow; the rays are largely responsible for the absorption seen in this direction.

Note that all of the heartwood and much of the sapwood is left unpreserved by the brushing or spraying method. When the post is part of a fence, the ground line is where the combination of air, moisture, wood and fungal source meet, and it is in this area that the risk of decay is greatest (see above section). Even a shallow split in the post will expose untreated sapwood, and allow decay to start.

Brushing and spraying are not good treating methods for preserving wood exposed to high risk of decay, such as for ground contact uses.

Cold soaking or steeping

The term cold soaking is used when an unheated oil solution of preservative, such as penta or copper naphthenate, is used. The term steeping is used for treatments of wood by preservatives in a water solution. The process consists of partially filling an open tank with preservative and immersing a dry, round fencepost in the tank. The post floats, so it must be weighted down to keep it sub-merged. The post is soaked for 24 or more hours, then removed. If we cut it lengthwise as before, the pattern of penetration using this treating method may look like Figure below. Note that both end-grain penetration and radial penetration are better than that obtained by brushing. Cold soaking or steeping has three avantages over brushing or spraying:

1. It allows a longer time for absorption to occur.

- 01. By holding the post below the surface of the preservative, a slight pressure is created which helps to force the preservative into the wood cells, thereby enhancing ordinary capillary action.

- 02. It is easier than having to rebrush or respray the post with more preservative at various intervals during the 24-hour treating period.

Unfortunately, although the penetration of preservative by soaking is better than by brushing, the ground-line area is still insufficiently-treated to provide long-term protection. Soaking was previously used commercially for treating fenceposts and rails, but pressure treatment has replaced it. Today, there are two principal uses for this treating method:

1. For exterior millwork such as window frame components. These parts get enough end-grain penetration to protect the very susceptible joints of the completed frame from decay in service.

2. For thin wood materials like trellis slats or lath panels for fencing. Modern pressure treatment, however, will give even better protection.

Vessel for soaking

Soaking of poles in hot preservative

Thermal process or hot-and-cold bath

When using the cold soaking or steeping method, a dry fence post was submerged for 24 hours in a tank of preservative at ambient (existing) temperature. With the thermal process or hot-and-cold bath, the same equipment is used, but the preservative is heated with the post in the tank (taking precautions against fire if it is oil-based). As the fencepost heats up, air in the wood expands and bubbles out, escaping through the preservative liquid into the atmosphere. The preservative is heated until no more air escapes from the post, and then the whole tank and submerged post is allowed to cool down. This process can also be completed in 24 hours. Figure shows the effect of this treatment on preservative penetration. There are several ways to use the thermal process. It is not necessary to use just one tank in which to heat and cool the preservative for each batch of poles or posts treated. Two storage tanks and a separate treating tank can be used. One storage tank is insulated for the hot preservative and an uninsulated tank isused for the cold solution. Posts or other wood products are placed in the treating tank and soaked in the hot preservative solution for about 6 hours. Then the hot liquid is pumped back into the insulated tank and the cold preservative from the other storage tank is flooded around the wood products still in the treating tank. This system requires more equipment than cold soaking, but saves time and energy, lowers labor costs and provides better treatment.

The thermal process produces much better penetration than treating by the brushing, spraying or cold soaking methods. There are several reasons for this improvement. Much of the air in the cell cavities is forced to expand and escape from the outer post areas. When the preservative is allowed to cool, air remaining in the cells shrinks. So a partial vacuum is created in the cells and atmospheric pressure pushing on the treating liquid helps force more preservative into the post. For this reason, the thermal process might also be considered a non-equipment-induced vacuum-pressure method. Also by using heat, viscosity of the preservative solution (especially those thick with carriers) is reduced and it therefore penetrates the wood more readily. To enhance penetration, incising or puncturing the lower part of poles with slots or small holes is a necessary preparation required by AWPA standards for the thermal process.

The thermal process is used mainly for treating poles with creosote mixtures. The species preferred for this process are those which combine narrow sapwood bands with naturally durable

heartwood. AWPA standards allow use of the thermal process for full-length treatment of some species (western red cedar).

In butt-only treatments, the poles stand with the butt ends immersed in the preservative to a depth one foot greater than the eventual ground line.

Hot and cold bath

Vacuum Pressure Methods

Conventional vacuum-pressure methods use pumps to create vacuum and pressure, thereby producing high pressure gradients and operator control over the process. By contrast the thermal process is limited to atmospheric pressure alone. However, by means of pumps, 10-12 atmospheres of pressure can easily and safely be produced. This is equivalent to about 140 to 175 pounds per square inch (psi) in a treating retort or cylinder. Figure indicates the penetration of preservative that might result from vacuum-pressure treatments. Although there are various vacuum-pressure methods available such as the Double Vacuum Process and the Mississippi State University Process, the principal methods used by the U.S. pressure-treating industry are:

Full cell process (Bethell process)

Full cell process (Bethell process)

Empty cell processes (Lowry and Rueping)

Empty cell processes (Lowry and Rueping)

Modified full cell process

Modified full cell process

Full cell process

This is the simplest and most common of the vacuum-pressure processes. It was developed by John Bethell in 1838. The full cell (or Bethell) process is used for most of the pressure treatments using chromated copper arsenate (CCA) and pentachlorophenol-based (PCP) preservatives, and a good proportion of the treatments with creosotes.

Features of the full cell process include:

It gives the deepest possible penetration and the highest loadings (retentions) of preservative with easily-treated species. Virtually all of the air in the wood cells can be replaced with preservative. Sometimes this may produce a higher loading than necessary

It gives the deepest possible penetration and the highest loadings (retentions) of preservative with easily-treated species. Virtually all of the air in the wood cells can be replaced with preservative. Sometimes this may produce a higher loading than necessary The degree to which penetration and retention of preservative occurs depends on the permeability of the wood. For effective treatment, some species may need special preparation such as incising, steaming, or Boultonizing, which are described in a later section of this lesson.

The degree to which penetration and retention of preservative occurs depends on the permeability of the wood. For effective treatment, some species may need special preparation such as incising, steaming, or Boultonizing, which are described in a later section of this lesson.

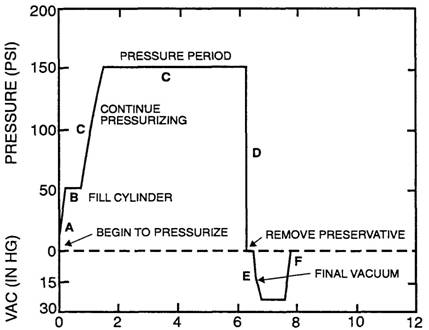

No vacuum-pressure process is more effective than the full cell in maximizing the uptake or penetration of preservative. The sequence of procedures used in the full cell process is shown in Figure, and is summarized below:

- Enclose dried wood (timbers, lumber, poles, etc.) in a pressurable cylinder or retort.

- Use a vacuum pump to remove most of the air from the cylinder. Hold a partial vacuum to allow air to be removed from the wood cells.

- Without releasing the vacuum, allow the cylinder to fill with liquid preservative.

- Apply pressure to the preservative to force it into the wood cell spaces previously occupied by air, now occupied by a partial vacuum.

- When the desired and measured amount of liquid preservative has been absorbed, release the applied pressure and drain the cylinder (initial drain).

- Apply a "final" vacuum to expand the air remaining in the wood. This forces excess liquid to exude from the surfaces

and run off.

G . Release final vacuum. As the remaining air in the cells contracts, much of the surface wetness will be reabsorbed into the wood (this reduces dripping later).

- Remove the treated wood products from the cylinder

- Empty cell processes (Lowry and Rueping)

-

For some purposes, it is necessary to ensure deep penetration of preservative without leaving all the cells full of preservative. An example would be coal tar creosote treatment for an above-ground use, such as fence rails, which require a retention of 8 pounds per cubic foot (pcf) in accordance with AWPA Standard C2. A full cell process, giving full-depth penetration of sapwood, would likely produce a retention of 12 pcf (4 pounds more than required).

To ensure good depth of penetration, the empty cell process forces more creosote intowood than is needed, but then removes the excess to leave the average retention desired. Look at Figures for the sequences followed during treatments with the Lowry and the Rueping empty cell processes. Both treating methods are similar to the full cell (Bethell) process except they omit the initial vacuum stage.

The Lowry Process is named for Cuthbert Lowry (1906, U.S.A.) In this process, after the wood has been closed in the cylinder, preservative is pumped in, and no air is allowed to escape. As the cylinder fills with liquid and pressure is applied, the air in the cylinder and in the wood cells is compressed into a smaller and smaller space. When the desired pressure is attained, air in the cells will occupy about one-tenth of the cell voids, and preservative can gradually fill up the other nine-tenths. The process then continues exactly as the full cell process, but the air compressed inside the wood expands when the pressure is released, thereby forcing some preservative out of the cells and eliminating overloading. The end result is that many cells are “lined” with preservative rather than “filled.” The final vacuum period can be used to extract more or less preservative as needed, so it acts as a retention control stage. The word “empty” in the term empty cell process is a poor description because cells are partly filled with preservative, in contrast with the word “full” which appropriately describes the full cell process.

The Lowry process is mainly used for treating wood with creosote, creosote/PCP mixtures and PCP preservatives.

The Rueping process is named for Max Rueping, (1902, Germany). This process is similar to the Lowry process. Here an air pressure higher than atmospheric is first applied to the closed cylinder and its charge of wood. The air pressure is generated by a compressor. A typical pressure used is four to five times atmospheric (about 60 psi). Treatment then continues as with the Lowry or full cell processes, but the amount of preservative removed (as the air compressed in the cells expands) is greater than in the Lowry process. This provides the necessary degree of penetration with even less final retention of preservative. The Rueping process also is mainly used with creosote, creosote/PCP mixtures and PCP preservatives. Other benefits of empty cell processes are:

The final weight of treated wood is reduced compared to full cell treatment.

The final weight of treated wood is reduced compared to full cell treatment.

A cost saving is realized from the use of less preservative chemical and carrier liquid.

A cost saving is realized from the use of less preservative chemical and carrier liquid.

Modified full cell process

This process is an adaptation of the Bethel1 process for use with waterborne preservatives like CCA. It, too, achieves full sapwood penetration with a reduction in the weight of water left in the wood. This is important if the wood is to be shipped after treatment, without thorough air-drying or kiln-drying. The lower weight of the treated wood is reflected in lower shipping costs.

The modified full cell process calls for a lower degree or period of initial vacuum than the full cell. By leaving more air in the cells, a greater amount of absorbed preservative is rejected when the pressure period is over.

The concentration of CCA solutions can easily be changed, either by adding more CCA concentrate or more water. Usually higher concentrations of CCA are used with the modified full cell than with the full cell

Treating schedule of the Lowry (empty cell) process.

Lowry (Empty Cell)

Process

A Fill cylinder with preservative at atmospheric pressure B Pressurize cylinder to maximum and maintain until retention is reached

C Release pressure and withdraw preservative D Apply final vacuum E Release final vacuum

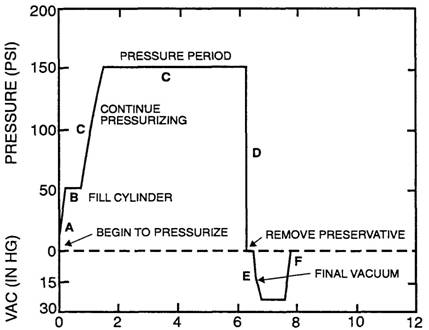

Treating schedule of the Rueping (empty cell) process.

Rueping (Empty Cell)

Process

A Partially pressurize cylinder B Fill cylinder with preservative C Continue pressurizing to maximum and hold until retention

is reached

D Release pressure and withdraw preservative E Apply final vacuum F Release final vacuum TIME (HOURS)

process, and essentially the same weight of CCA chemical is left in the wood, but less water. A 20% reduction in overall weight of wood products treated in this way will give similar percentage savings in the cost of shipping undried products.

Technical Note: Before shipping, it is essential that treated wood has stopped drip-ping. A properly drained and covered drip-pad is used for this purpose. In the case of CCA preservatives, at least 24 hours should be allowed for chemical fixation to take place. Fixation time is appreciably longer in cold weather.

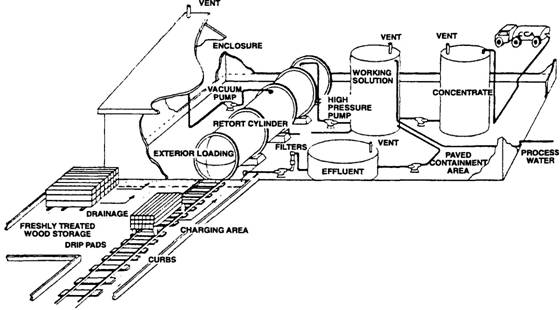

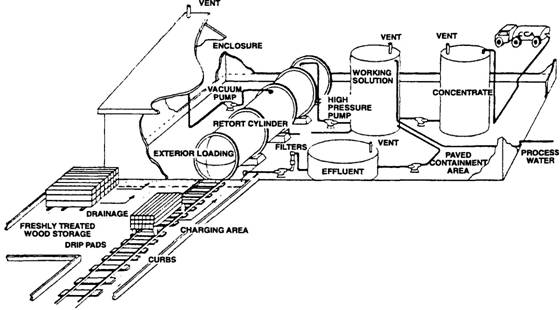

Vacuum-Pressure Treating Plant

Equipment

Equipment used to apply preservatives under pressure is not standard in design, but most systems are capable of wood treatment by the full cell, Lowry or modified full cell processes. The compressed air required for the, Rueping process is not always available, but this process is not widely used.

The major item of a pressure-treating plant is the treating cylinder or retort, which can vary in size but is commonly 4 to 8 feet in diameter and 30 to 150 feet long. Auxiliary equipment usually includes a boiler, dry kiln, pumps, tanks, gauges, thermometers, control-lers and valves (see Figure 5.6).

Specialized accessories such as incisors, steam generators, trams, hoists, lift trucks, debarkers, shavers, machinery for adzing and boring, condensers and water purification equipment are often needed. These are not usually directly connected with the pressure process, but rather with preparation of the wood items for treatment, or for pollution prevention.

Figure 5.6 Conceptual diagram of CCA pressure-treating facility.

Preparation or Pretreatment of Wood for Vacuum-Pressure Application

Before wood cells can accept sufficient preservative liquid to satisfy preservation standards, the product to be treated must meet the following conditions:

1. There should be no bark or inner bark, paint, varnish or other impediments to surface penetration of preservative.

2. The wood product should be air-dried or kiln-dried to an average moisture content of 25% or less, unless pressure treatment is preceded by steam conditioning (drying green wood in the cylinder by steaming) or Boultonizing, described in the next section.

Preparation or Pretreatment of Wood for Vacuum-Pressure Application

Before wood cells can accept sufficient preservative liquid to satisfy preservation standards, the product to be treated must meet the following conditions:

1. There should be no bark or inner bark, paint, varnish or other impediments to surface penetration of preservative.

2. The wood product should be air-dried or kiln-dried to an average moisture content of 25% or less, unless pressure treatment is preceded by steam conditioning (drying green wood in the cylinder by steaming) or Boultonizing, described in the next section.

3. Incising should be carried out whenever the treating standard calls for it. AWPA standards require incising of many "difficult to treat" species to increase surface penetration and retentions (see the Standards for details).

Debarking

-

Boultonizing

This conditioning or drying method is used with creosote preservative. It is an alternative to conventional wood seasoning, an essential step for good penetration. It is accomplished by enclosing green wood products (poles, crossties, timbers, etc.) in the treating cylinder and introducing creosote at 210° F to 220° F while applying a vacuum. Water, removed from the wood by evaporation, is then condensed in special equipment outside the cylinder. Since the boiling point of water (in the wood) is lower under a partial vacuum than at atmospheric pressure, drying can occur rapidly at temperatures below 212" F (depending on the proportion of sapwood to heartwood). Although Boultonizing does not thoroughly dry wood, it improves the ability of many wood species to accept preservative by the conventional full cell process which follows Boultonizing. (See AWPA standards for commodities and species allowed for Boultonizing .

Steaming

In this preconditioning process, green or partially seasoned wood items are first subjected to pressurized steam at about 240" F for a limited time. The AWPA standards define the species, temperature and time allowed. Over-steaming reduces the strength of wood, often seriously, but a controlled steaming process, like Boultonizing, can reduce the moisture content of green wood products to a condition acceptable for treatment. Steaming is not used as extensively as it once was, and is mostly practiced today with west coast softwood species.

Incising

This is a process of mechanically punctur-ing the outer surfaces of wood products, usually poles, crossties, timbers and some-times lumber. Slots or holes of a controlled depth and spacing are made. This improves the uptake of preservative in "difficult-to-treat" species, and helps provide a treated zone around the outside of the wood item. AWPA standards specify which species and commodities should be incised.

-

Units of Measure Used in Wood

Preservation

Units of vacuum

The science of physics defines a total vacuum as a condition in which there is an absence of matter, such as in a container. In pressure terms, a total vacuum has zero pressure, that is, there are no gas molecules to create a pressure on the container. The only easy way that vacuum can be measured is by comparison with a higher pressure, usually atmospheric pressure (explained below). The units used to express vacuum are inches of mercury or in. Hg (Hg is the chemical symbolfor mercury). Mercury is used because it is a very dense liquid. If the bottom end of a glass tube is inserted into a container of mercury and a vacuum is created at its upper end, mercury will tend to move up the tube. The height of the column of mercury in the tube, above the level of mercury in the container, can be measured with a rule.

When no vacuum is applied, the mercury is the same level both inside and outside of the tube. A reading of 0" Hg tells us there is zero or no vacuum. As the vacuum is increased, mercury rises inch by inch inside the tube (1" Hg, 2" Hg, 3" Hg, and so on). The maximum possible vacuum (no molecules of gas) would give a reading of 30" Hg, if the air outside was average barometric pressure found at sea level.

Note: A typical initial vacuum level for the full cell process is 22" to 28" Hg.

In practice, the gauges used with treating equipment have rotating needles or moving recorder pens. Although they are not mercury-filled, the gauges are calibrated against a mercury column.

Units of pressure

Although there is no real reason why pressure could not be measured with mercury, as for a vacuum, it is normal to express pressure as the force, in pounds, exerted by a gas or liquid on one square inch of surface; that is pounds per square inch or psi. The air around us is at a positive pressure. Compared to a total vacuum, atmospheric pressure at sea level averages about 15 psi. Pressure gauges normally read zero if there is no pressure above atmospheric pressure. This is referred to as a gauge pressure of zero (actually it is an atmospheric pressure of 15 psi). The gauge pressure used when treating wood is normally 150-200 psi.

Units of liquid volume

Preservative volumes are measured in U.S. gallons.

Units of wood volume

In the treating process actual cubic feet of wood material is the correct unit of volume to use for the treatment charge. This is the volume obtained for each individual item by measuring its actual dimensions (whether lumber, poles, timbers or plywood), then calculating the volume in cubic feet of each item and adding them all together. This explanation must be emphasized because the nominal dimensions used in the lumber trade are seldom the actual dimensions of the lumber. For example, if you calculate the volume of a 10 foot 2x4 and assume it is 2"x 4"xl0" you would get 0.555 cu. ft.

This calculation is correct for a piece of lumber with actual 2"x4"x10' dimensions. However, 0.555 cu. ft. is incorrect for determining the volume of a treatment charge because 2x4 lumber, when dressed or planed, actually measures only 1-1/2" x 3-1/2" in cross-section. The stated lengths of lumber, however, are actual lengths. So the correct volume of a 10 foot 2x4 to be used for determining treating charge volume is 0.365 cubic feet:

The error obtained in calculating the volume of this one piece of lumber was 52% too high and could have seriously affected the amount of preservative required for the charge.

Units of retention

Retention is always expressed in pounds of preservative chemical per cubic foot of actual charge volume (lb/cu. ft. or pcf). With creosote, which is both the preservative and the carrier liquid, the total weight of creosote in the wood is used in computing the pcf retention. Not all of the wood in a charge will accept the same amount of preservative, therefore several pieces should be tested to ascertain average retention. Most other preservatives, particularly PCP, ACA and CCA, are carried into the wood in a petroleum solvent or water. The weight of the carrier for these preservatives is relatively unimportant in deciding the retention of the preservative. What matters is the weight of active chemical per cubic foot of wood.

Retention of pentachlorophenol is expressed as lb. PCP/cu. ft. or pcf PCP.

Retention of chromated copper arsenate preservatives is expressed as lb. CCA/cu. ft. or pcf CCA. All CCA preservatives areconsidered to be 100% oxide materials, that is, the water carrier is ignored and the preservative is considered to conform with the formula required for CCA types A, B or C (given in section above).

Units of shipping volume for wood items

Lumber is conventionally sold by the board foot; poles by length and diameter at the butt, at the tip or six feet from the butt; plywood and other panel materials by the square foot and thickness.

The prefix M usually means one thousand, and BF or b.f. refers to board feet. Therefore:

1 MBF = one thousand board feet

1 MMBF = one million board feet

Board feet is the common unit of measure for marketing both untreated and treated lumber, but in the wood-treating process itself the b.f. unit is not used.

Units of penetration

Penetration is measured in inches or in percentage of total sapwood penetrated. To see the extent of preservative penetration, increment borings are taken out of sample pieces of treated wood. Depth of creosote penetration is usually easy to see because of its color. With PCP and CCA, spray-on chemicals that enhance detection of the preservative color are available. Penetration and retention of preservative is usually more effective in roundwood products than in squared stock because of their higher proportion of sapwood. The AWPA standard for each commodity and species details the penetration demanded of a given preservative.

¬ read more